As digital printing extends its reach into more and more applications, an issue that’s growing in importance in many sectors is brand colour accuracy. Simon Eccles charts a course for correct colour.

Customers who have special house colours like to have them reproduced exactly the same everywhere.

This tends to be a particularly big issue in digital packaging and label production, but it also matters for corporate work such as brochures and company reports which may be printed by general-purpose commercial printers. However, unless you tell it otherwise, a digital front end (DFE) /RIP will output each spot colour as a separate colour. If your press doesn’t have a spot colour facility, these need to be converted to process colours at some point in prepress. Nearly any DFE can take named spot colours (usually referenced by Pantone numbers), look them up in a table, and output separations as combinations of the printer’s own process colours – normally CMYK but sometimes with five, six or even seven colours.

The problem comes when a brand colour cannot be reproduced accurately enough from standard process colours. In the analogue printing world the solution is to print the difficult colour as a separate ‘special’ ink on the press. However most digital presses can’t run specially mixed colours, and even for those few that can, the economics aren’t brilliant – unless of course you can add it to the bill.

Extended gamuts help

However, the ‘standard’ CMYK gamut of many digital presses exceeds that of litho or flexo presses. This lets them emulate conventional processes, generally working to the Fogra 39L de facto standard used for litho on coated papers. Depending on whose figures you believe, Fogra 39L litho lets you output perhaps 65% of the Pantone coated colour set. However, some digital CMYKs have a much wider gamut, and get this figure up to between 85% and 90%. This allows colours to be printed with a CMYK digital press that would need a special colour in litho or flexo.

If you’ve got a wide gamut press, then the separations need to be made to take advantage of this, via spot colour replacement. Ideally the customer would supply files as RGB plus spots and let the prepress sort it out. That may be a step too far for some agencies who like to supply CMYK in order to control black values.

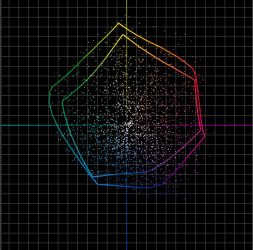

Just how wide a gamut you get varies between the type of digital press. For instance Fujifilm likes to demonstrate the particularly wide CMYK gamut of its Jet Press 720S and new 750S inkjet models; it claims that 90% of Pantone colours can be matched.

While some digital dry toner presses offer five colours (or six in the case of the Xerox Iridesse) these tend to be used for either white or clear toners, or ‘embellishment’ effects such as metallics. Ricoh’s fifth colours can also be yellow or pink ‘neon’ fluorescents, which do extend the gamut in those specific hue ranges when mixed with the other process colours but are more aimed at special effects work.

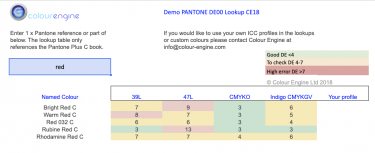

Color Engine’s online tool lets you see how good a match a profiled press, ink and paper combination can get to a specific Pantone

Special shades

Extra colours offered purely for gamut extension are rarer. Xerox has offered orange, green and blue for the iGen 5 series, while Kodak offers a choice of red, blue or green ‘dry ink’ toners as gamut extenders on its Nexpress and Nexfinity presses and will make special toner colours to order.

‘With the addition of our fifth station gamut expansion inks, we hit 92% of Pantone colours within a delta-E of 3,’ says Len Christopher, Nexpress product manager. ‘This is usually the choice most customers make. However, we have also introduced the ability to supply custom colours, so a specific Pantone or swatch colour could be created for use as a fifth station colour. Unlike HP Indigo inks, these custom inks don’t have a short shelf life if properly stored, so can be used as needed over a longer period of time.’

HP’s Indigo liquid toner presses have long been notable in that most modern models have the option to run six or seven colours. These can be an extended gamut six or seven colour process set called IndiChrome, or, uniquely, they can run specially mixed inks to supplied order. You can even buy a kit to mix your own. What’s more it’s easy to change colours between jobs, and also to swap the laydown order, which until very recently was impossible on dry toner presses (only the newish Xerox Iridesse and Kodak Nexfinity offer some order flexibility). The downside of running more than CMYK on an Indigo is that it slows down the press as well as costing more in clicks.

Delta blues

Assuming you have a reasonably wide gamut process, whether just CMYK or with extra process colours, you’re going to want to know which colours it can and can’t match. As a general rule if you can print to within a measured colour difference (defined as a ‘delta-E’ or dE) of 2 or less of the target colour then the match looks identical to the human eye. Kodak quotes a dE of 3 as an acceptable match: actually most people only notice a difference with a dE of 5 or more. You can measure comparative print vs target swatches using a spectrophotometer and colour management software will calculate the dE value.

Any prepress RIPs or workflows will have built-in look-up tables that convert Pantone numbers to the nearest achievable results possible with the particular digital toner/ink pigments. They can often print swatch samples to show to clients. However they don’t necessarily tell you how close the match will be.

Another common issue is when printers are asked to match a previously printed sample that’s supposed to conform to a Pantone value but doesn’t. They need to determine what the colour is before they can match it.

Several suppliers offer ways to predict how closely a particular press/ink/substrate combination can match a given brand colour. For example Fujifilm’s XMF workflow is used for the JetPress 720S and 750S. Last November Fuji announced XMF Colorpath, a cloud based ‘brand colour optimiser’ intended specifically for spot colour conversions to the JetPress’ wide-gamut CMYK. A particularly useful feature is its prediction ability, allowing users to see in advance which press, ink and substrate combination allows the spot colours to be accurately printed, or if it can’t be. Xerox also has a software tool for the iGen 5 to identify how close a match you might achieve to a specified or measured colour.

Alwan Color Expertise, whose systems are supplied in the UK by Colour Engine, offers the Color Hub colour servers and utilities to convert various incoming colour definitions to profiled output sets. Colour servers are also offered by other companies, notably CGS and GMG, plus ColorGate (with Productionserver) that was recently acquired by Ricoh. EFI’s Fiery range is in the same category, except they are more commonly supplied as part of the printer vendor’s official choice of DFEs and some of them include extremely powerful RIPs for high speed digital presses.

A gamut comparison between Fujifilm’s JetPress (outer shape) and ISO standard litho colour gamuts (inner shape); the dots are individual Pantone Colours

Multi-press matching

A common reason to buy a colour server is that companies may have presses from more than one manufacturer. While the manufacturer’s own DFE will do a decent job and will have facilities for matching other presses from the same source, it won’t necessarily be able to match, say, a Xerox Trivor to a Ricoh Pro C7100. Third-party colour servers can be set up to match pretty well anything that’s capable of being matched.

Colour Engine has written an online utility that can predict the colour accuracy with any profile to give a Delta E value of how closely it matches a given target colour. Director Mark Anderton also says that Alwan’s Hydra Profiling ‘is massively relevant to anyone doing extended gamut printing. The amount of data needed, or mapping points, goes up massively between four and seven colours.’

Fellow director Malcolm Mackenzie adds that ‘A lot of digital printers don’t like having bespoke profiles for their substrates, as it either takes time for themselves or they have to pay consultants to do it and it still takes time on the press. With Hydra profiling, as long as the machine has been linearised, we can make a profile with 300 patches. That’s not many at all – an i1Pro hand-held takes about 10 minutes to measure and make a profile. What’s really key to getting the closest matches is accurately profiling the printer/media combination to start with. If you have a good profile then we can do all this other work about how well you can print a particular colour on a particular substrate.’

Bernd Rückert, product marketing manager for CGS in Germany, says ‘We have two products for brand matching. One is 10 years old, ORIS Press Matcher / Web. This works with any CMYK print device via its RIP/DFE. This has a base calibration, then the colour match. It works with RGB/CMYK and also takes care of spot colours in systems such as Pantone, Toyo Ink [or] HKS. As Press Matcher is for CMYK printers only, we upgraded it into ORIS X Gamut, which can handle up to eight colour channels in the printer.’

EFI has a utility for matching spot colours for printers that use its Fiery DFEs, says John Fennel, Fiery technical sales specialist. ‘Fiery Spot-On is used to take a colour value and match it to CMYK. Spot-On provides a graphical user interface which helps users to ‘zero in’ on the CMYK toner equivalents needed to create a desired spot colour for a given device. It shows a visual representation of the printed colour next to the target colour, together with the difference measured as Delta E. It also enables users to create custom colours with a specified name and CMYK value.’ EFI’s Profiler Suite can also be used to make a visual match between different makes and models of press or process.

GMG introduced its OpenColor tool a couple of years ago, intended to primarily to aid spot colour separations for packaging but relevant to any digital printing. GMG’s business development manager Paul Bromley says that the USP is that this is now ‘truly spectral colour,’ rather than LAB (a colour definition system based on human vision). ‘Spectral data is 1100 times more accurate than CIE LAB,’ he claims. ‘OpenColor makes a profile, and then hands it to a third-party separator which can do extended colour gamut separations.’ The profiling software reads GMG’s ‘smart ministrip’ colour patches which can be placed around the margins of a commercial job, rather than printing special calibration runs. ‘Our ColorServer can also match from press to press, for instance for a job that could start digital, then continue as flexo or litho, or the other way round,’ says Mr Bromley.

Like other aspects of colour management, it can seem quite complicated but commercial digital presses, whether toner or inkjet, can do a pretty good job of matching brand colours with the right software and set-up, even when you can’t just mix a special ink for them.