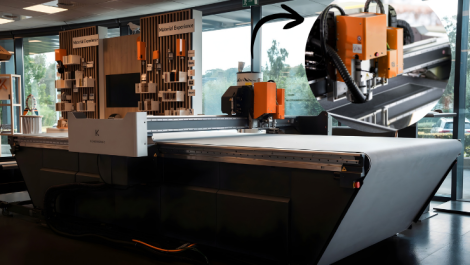

Xeikon has developed its own X-800 front end, seen here with a Xeikon 9800

Digital Front Ends promise a workflow in a box solution capable of driving a production digital press.

Every digital print engine comes complete with a digital front end or DFE controller that’s been developed alongside it to help squeeze the full capability out of that engine. The DFE basically consists of a RIP for the specific print engine plus a number of prepress tools such as colour management and imposition, effectively a complete prepress workflow in one box.

It’s mostly software but is supplied as a control station with the associated server, processors and RAM chosen to match the capabilities of the press and the individual customer’s intended applications. The level of hardware – and the degree that it’s tailored to the customer’s needs – depends largely on the volume of data that has to be crunched.

As a result, there is no single DFE that can drive multiple digital presses. That said, EFI comes the closest as it has worked with several of the press manufacturers to develop Fiery Servers for particular models. This is mostly because companies such as Xerox or Konica Minolta want to offer a wider choice to their customers besides their own DFE.

Alan Clark, product and solutions marketing manager for Xerox UK, says that there’s little difference in cost or capability between the EFI Fiery Server and Xerox’s own FreeFlow Server, so the choice is down to customer preference. He points out that the FreeFlow server was first developed over 20 years ago to drive Xerox’s monochrome printers and so many customers have become comfortable using it even as they have moved to higher volume and colour printers.

That said, one of the advantages of the Fiery Server is its sheer universality, as John Henze, vice president of marketing for EFI, explains: ‘With Fiery driven printers the same common workstation can manage printers from several vendors and that’s a huge deal to the customers for training and operator management.’

Hardware and performance

The front end will be designed to match the performance of the printer, so that engines meant for higher duty cycles will come with more powerful servers. However, Martin Bailey, chief technical officer for RIP developer Global Graphics, says that there is a split between light production and high volume printers and that it’s not practical to simply scale up a RIP that was originally designed for light production workloads. He points out: ‘The volume of data is huge and has to be managed in some way between the RIP and being sent to the printheads.’

In addition, some applications will require more raw processing power than others. Thus photobooks put a heavy workload on the front end with each job likely to include large numbers of image files, spread over many pages, which must all be RIP’d for just a single copy to be printed before the next job.

Most front ends will use hard disks or RAM to hold the data before sending it to the print engine but Bailey says that you can’t simply add more processors and disks as you need to be able to track all the data, noting: ‘You have to make sure that all the bits can talk to each other at speed.’ This is particularly important with variable data applications where static page elements will have to be cached ready for the RIP to call on them as needed.

However, in some cases the DFE is only taking part of the processing load. Thus, Xeikon’s X800 RIP creates an imposed print-ready file, but the final screening and colour calibration happens on the fly within the print engine itself based on the built-in spectrophotometer.

Inkjet and high volume

There’s a growing number of high speed inkjet presses and these will have their own demands on the front end. Mark Hinder, market development manager for Konica Minolta, says that inkjet is very different to toner: ‘To get 1200 x 1200 dpi through the heads you are firing lots of very tiny nozzles and that’s an enormous amount of data.’ Consequently, Konica Minolta has opted to develop its own front end specifically for its upcoming KM-1 B2 digital press.

HP also had to confront similar problems when it first launched the PageWide Web Press. Guy Thompson, business development manager for packaging for HP’s web press, says that the team developing the DFE was aware of the roadmap for wider, faster machines to come with all the high volume data handling that would entail. So the team drew inspiration from an earlier DFE developed to allow the Indigo presses to cope with large numbers of image-rich photobooks without creating a bottleneck, by stripping out features and automating as many decisions as possible. Thompson notes: ‘As we scale up in production we often find that the DFE goes in a more managed environment and the operator is expected to do less and less.’

The system, which is based around the Global Graphics Harlequin RIP is designed to be extremely scaleable allowing HP to simply add more RIPs to the core system. Thus HP now offers ten levels for this front end with different numbers of servers to take into account different use cases. Thompson explains: ‘So someone doing short run books of 100 to 200 books doesn’t need a very big DFE. But the mail people with transactional and direct mail where every page is different need a lot more horsepower.’ The highest level includes 15 RIP servers with each server running 12 RIPs for a total of 180 RIPs running together. Thompson adds: ‘The assumption is that you are getting a book and can split that up to each of the RIPs so that they are processing in parallel.’

Data streams

Naturally, most workflows are designed to handle PDFs, which these days includes PDF/VT for fully variable jobs. But there’s still a lot of demand for IPDS for applications such as transactional printing so some vendors offer this as an option. Xeikon offers customers a choice between its X800 DFE, which is built on Adobe’s PDF Print Engine, or an IPDS front end. Jeroen Van Bauwel, director of product manager for Xeikon, says that there’s a different philosophy behind the two systems: ‘With an IPDS workflow you don’t want to give the operator tools to modify the files so this is all handled by the print server and it’s different technology with a different interface.’ However, he adds that the two are moving together: ‘Ten to fifteen years ago IPDS was a purely black and white workflow but now there are lots of tools for colour management and we have recently added PDF support within IPDS.’

Xerox also offers an IPDS option to its FreeFlow Server. Joe Rouhana, director of Xerox’s production solutions line of business, argues that some applications require a native controller, saying: ‘You want to consider bi-directional communication with IPDS so the print server is certified to handle full IPDS natively. Sometimes a converter will convert the whole job but you really want to handle the job at a page level.’

EFI has worked with a number of printer manufacturers to offer versions of its Fiery Server, which all share a similar interface.

Integration

Most DFEs include prepress workflow functions but the ability to connect to a wider workflow from web-to-print through to finishing is also important. This is one area where EFI’s Fiery Server really scores through the level of integration that it offers. The company has a large number of MIS, covering different applications with support in many geographic market and has created Productivity Suites around these MIS to drive tighter integration with other software including the front ends. Elli Cloots, senior product marketing manager with EFI, says: ‘We can integrate with other RIPs and front ends. With our MIS and Digital Store Front we get feedback so there’s synchronisation between the MIS and the Fiery and that integration allows for more productivity through automation.’

Most front ends rely on JDF/ JMF to take in job tickets and integrate with other systems. This also includes working with CtP workflows with some functions such as preflighting. However, the exact degree of integration varies from vendor to vendor and is likely to be tighter for more common systems.

There’s also a need to send data downstream for finishing, with most DFEs exerting control over inline finishing. Most systems can also print information from the job ticket as a barcode for offline finishing. HP has gone slightly further than most, developing a Direct to Finish extension for its Production Pro DFE. This integrates with JDF-enabled devices, as Gershon Alon, manager of HP Indigo’s workflow solutions, explains: ‘We have added a tab for finishing to the DFE so we know not only how many jobs we have to print but also the finishing plans for those jobs.’ The system calculates the finishing at the point of printing the job, so that it can take account of late changes. It takes into account the order that jobs will need to be finished in to group similar jobs together. Alon continues: ‘We print a cover page with a barcode. So, for example, we communicate to the guillotine exactly what the layout of the sheet is and the best cutting plan.’

Finally, it’s worth noting that although the front end may have started as a complete workflow in a box, there’s an increasing need to separate the prepress file preparation functions away from the machine operator. Decisions about how to structure work and job queues are more likely to be taken further upstream, particularly for high volume engines printing to a roll where the order the jobs are printed in will determine the order of the finishing operations. But the degree to which the functions of the front end can now be networked shows us just how deeply digital press engines are now integrated within a print factory’s total operations.