High-speed inkjet presses have always been seen as a disruptive force and as their image quality continues to improve this disruption is reaching more applications, says Nessan Cleary.

Since the introduction of digital dry toner presses some 20 years ago we’ve become used to the idea that digital mainly deals with short run while conventional offset printing is for long runs. This has held good even though run lengths in general are falling and “short runs” have become longer runs. But single-pass inkjet presses threaten to upset this balance because they have all the advantages of short-run printing but can also handle a high volume of work at a cost that could challenge the viability of offset, at least for some applications.

Ricoh Europe’s Business Innovations & Solutions director Erwin Busselot says that although inkjet printers were initially used for data-driven applications such as transactional and transpromo printing, commercial printers are now looking at these devices. ‘These people run continuous-feed inkjet as a commercial press. They will print a multitude of applications from posters on-demand to flyers, brochures and so on with their press. They think of it as a cut-sheet press in that the input might be continuous feed but the output is cut-to-stack ready for finishing,’ he comments.

This still means that there’s less flexibility in terms of substrate choice than with a cut-sheet press. But the higher speed of continuous feed translates into lower running costs and many customers are willing to give up some degree in choice of substrates if the price is right. In some applications, such as publishing, printers have got around this limitation by grouping individual jobs according to a common substrate.

Despite this, the main reasons that printers choose inkjet presses come down to the image quality, the speed and the running costs. It’s still the case that they will have to prioritise two out of these three factors as higher resolution generally comes at the cost of slower speed.

Mr Busselot contends that for most customers, the running cost and the image quality are the most important factors, pointing out that inkjet can still be competitive against offset even if the press is slower because most continuous-feed inkjet machines offer monthly volumes in the order of several million pages, which is enough for most European printers. He also points out that digital printing can distort the costs: ‘So in book printing, digital allowed customers to move away from printing and then selling to selling and then printing, which gives a lot of advantages to the price.’

Ink quest

Nonetheless, the main trend is the continuing development of inks that are capable of printing on offset coated stocks. This allows printers to cut running costs by avoiding the more expensive dedicated inkjet stocks and gives greater flexibility in stock inventory to anyone putting in an inkjet press alongside an offset machine. Using the same stock also makes it easier to switch jobs from one press to another. At the same time, most of the new presses have improved their systems so that they can put more ink on the media, leading to better image quality, without the mottling and curling effects that typically follow when you put too much water on paper.

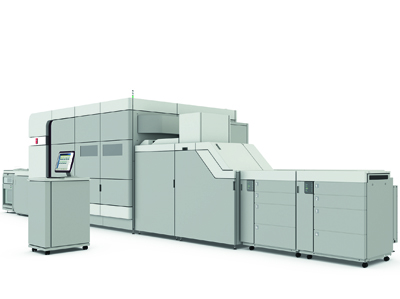

Thus Ricoh has just launched the Pro VC70000, which is essentially an updated version of the existing VC60000 but with a new ink set that allows it to print to a wider range of papers including uncoated and offset coated as well as inkjet treated or inkjet coated papers. Ricoh has also redesigned the drying unit. Tim Taylor, head of Ricoh’s continuous feed production printing, explains: ‘We have added lots of little heated rollers that go around the outside of the drum. The paper goes in and out of different rollers so that it’s constantly being straightened out, which keeps the sheets flat.’

Ricoh claims that the new inks also have a wider colour gamut, which should give customers a choice between printing more vibrant images or running at a faster speed while still producing reasonable quality. The press can be run at 150m/min at 600dpi, though it can also produce 1200dpi images, albeit at a lower speed.

Ricoh has worked with Screen to jointly develop the VC60000, with Screen also selling its own version of this press as the TruePress Jet 520HD. However, Screen has also developed its own SC ink to allow the press to run with standard offset coated papers, without the need for pre-treatment.

Earlier this year PrintOnDemand Worldwide became the first British customer to adopt this ink, using the 520HD to print books.

Managing director Andy Cork says: ‘The HD press combined with the SC inks was the turning point in getting PODWW to shift from a toner-first to an inkjet-first company. The ability to print directly onto offset coated paper, without the need for pre-treatment or expensive bonding agents means we can meet our customers’ quality expectations whilst making a margin.’

Mr Cork adds that there’s little difference in quality between a litho press and the 520HD: ‘The speed and the impressive uptime of the press means we can produce in excess of 4000 books in a shift, even with our average run-length of 1.75 books, with a focus to deliver them same-day/next day depending on the product line.’

Xerox has also thought about the need to print to offset stocks, introducing a Fusion ink option for its Trivor 2400 inkjet press. This allows the press to take offset coated papers without any further coating. The Trivor is a single engine duplex press that takes a 511mm width web. It can produce 100m/min at 600 x 600dpi with the choice to increase either the speed at lower resolution or the resolution at lower speeds.

Canon’s main inkjet offering is the Océ ProStream, which was launched last year. This has a print width of 540mm and a relatively slow speed of 80m/min. Canon says that it’s capable of producing 35 million A4 pages per month. There’s a high-definition 1200dpi printhead, that Canon calls DigiDot. It’s said to produce sharp images with fine details, smooth greyscales, as well as large areas of solid ink coverage.

But the most interesting element is its pigmented polymer ink. This uses a latex component that melts during the drying and forms a film on the surface that protects the pigment on the surface of the paper. The press also uses Canon’s ColorGrip, which is essentially a primer that’s jetted alongside the CMYK inks. As a result, the press works with both standard coated and uncoated offset papers from 60 to 160gsm. Canon claims that this new ink set can match or exceed offset colour gamut for high quality applications. This is matched by a non-contact drying system that allows for dense ink coverage.

Sheetfed alternatives

Canon has also developed the Océ VarioPrint i-series of B3 sheetfed inkjet presses. The series includes the faster i300 and the i200, which both use Kyocera printheads printing at 600 x 600dpi but with variable sized droplets to produce an apparent resolution of 1200dpi.

Earlier this year Canon introduced new iQuarius MX inks for these presses to allow them to print directly to offset coated stocks. This opens up the applications these presses can handle, making them suitable for things like higher quality books and manuals as well as the transactional and direct mail uses they were originally designed for.

Fujifilm has been clear from the start that the main target for its single-sided Jet Press is commercial offset printers. Fujifilm’s argument is that most B2 printers are used to a ‘work and turn’ workflow so they can quickly put the printed sheets back through the press, using the barcode feature to ensure that the correct front and back images are matched up. However, Fujifilm has enlarged the original Jet Press 720S to create a new 750S. This was shown as an early version at the Igas show in Japan earlier this summer, and will be commercially available in Japan this autumn and in Europe a few months later. The Jet Press 750S takes a larger sheet size of 750 x 585mm, big enough to fit six US letter size pages. It’s fitted with the latest generation of the Samba printheads, delivering 1200 x 1200dpi, as well as a new, more compact drying system with a heated conveyor belt that uses 10% less energy. The net result is an increase in speed to 3600 sheets per hour, up from the 2700sph of the 720S. It uses the same CMYK Vividia aqueous pigment inks.

The other major application for single-pass inkjet printing lies in the growing digital packaging market. But it is worth noting here that there’s a very wide range of substrates used in packaging. For now, most inkjet presses are aimed at corrugated, folding carton or other paper-based types of packaging. Flexible films, which are widely used throughout packaging, are more challenging for water-based inks. But this is where most vendors are concentrating their R&D spending so we should see continuing developments in inks, leading to better print quality on a wider range of substrates.